Physical puzzles¶

Higher-dimensional (“virtual”) puzzles naturally exist in more than 3 dimensions. Physical puzzles are a way to make a 3-dimensional object that functions similarly to this higher-dimensional puzzle. They must be able to perform the moves of the puzzle, so everything that can be done on the virtual puzzle can be done on the physical puzzle. However, most physical puzzles are able to perform other moves that are not allowed on the virtual puzzle, and these must be disallowed by the rules of operating the puzzle. The more rules a puzzle requires, the more complicated operating it becomes, and it becomes less interesting. The most interesting and natural physical puzzles implement as many of the restrictions as possible as part of the mechanism.

Warning

The relationship between virtual and physical puzzles is reversed from what it usually is in 3 dimensions! In the normal case, the physical puzzle has a mechanism that restricts the possible moves, and the unrestricted moves become legal, and a virtual simulation of the puzzle should copy the moves from the physical puzzle. However, when constructing a virtual higher-dimensional puzzle, the legal moves are defined abstractly, and the physical puzzle needs to have restrictions applied to it by rules.

The simplest way to construct a physical puzzle is to create the most unrestricted object possible, and apply all restrictions via the rules. We can make one physical piece for each sticker of the virtual puzzle, and observe on the virtual puzzle the permutation of the stickers when applying one move. When we allow this set of moves on the physical puzzle, we get sticker soup. This is the simplest way to construct a physical puzzle, and since it has no mechanism at all, the rules of operation are just the permutation. This is generally considered uninteresting.

Since in a virtual puzzle, stickers are part of pieces and cannot be separated, it makes sense to make this a restriction of a physical puzzle as well. In this case, a physical piece is a virtual piece. This applies some design constraints to the puzzle. On the virtual puzzle, there are generally moves that reorient a piece, which has the effect of permuting its stickers. This produces the orientation group of the piece. A physical puzzle built like this must have pieces that can represent that symmetry group.

Melinda’s 24¶

The 24 has 16 pieces, each with 4 stickers. By performing moves on a virtual 24, a piece can be brought back to its position with any even permutation of stickers. (It is not just the monoflip because that assumes the rest of the puzzle is solved, which is not important here.) In three dimensions, a tetrahedron with its four vertices representing the stickers has the same symmetry. (This is not a coincidence; a 24 built on the surface of a hypersphere will have its pieces be spherical tetrahedra with the stickers at the vertices.) Thus, the pieces of Melinda’s 24 have tetrahedral symmetry.

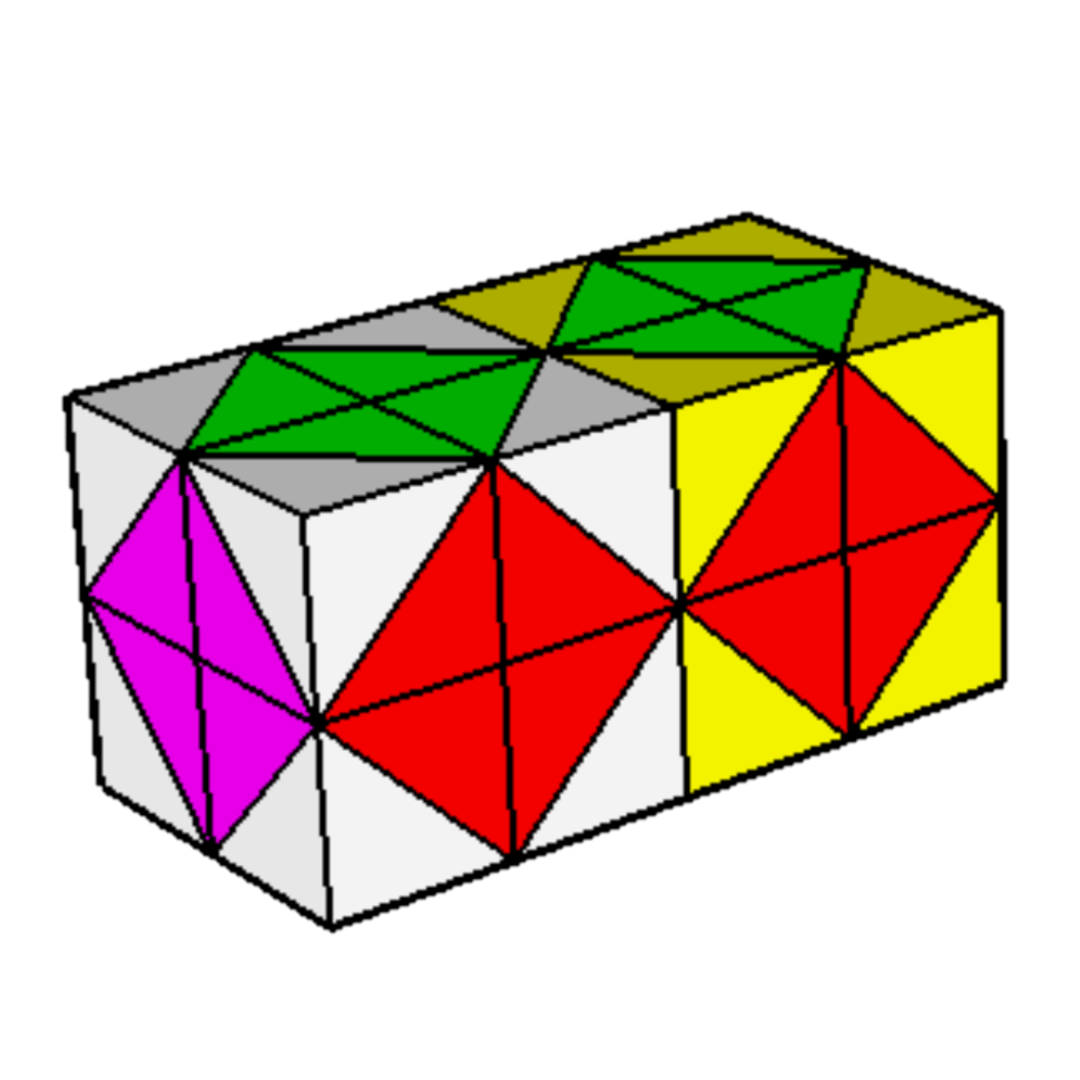

This is not the only design decision resulting in a usable physical puzzle. Since the pieces of the 24 can be arranged in two cubic layers, the pieces are cubes to allow them to stick together in this fashion. This makes many of the moves simply rotating one whole cube of 8 pieces, and the others rotate 4 pieces from each layer in a simple way. These moves are unable to swap a white or yellow sticker with a sticker of a different color, which means the puzzle simulates a cubic prism puzzle: a 23x21 cuboid, where the first three axes can turn into each other but the last one cannot in the same way that a 3x3x3x2 is restricted.

The virtual 24, on the other hand, does allow moves that take a white or yellow sticker to a sticker of a different color, and the pieces were designed so that this operation is possible. It would be possible to observe those moves, record which piece goes where, and apply that to the physical 24, but this is unwieldy. Instead, Melinda introduced a gyro, a sequence of actions that does the equivalent of a whole-puzzle rotation on the virtual puzzle, but takes a white sticker to a sticker on a different axis. Thus, other moves are accessible by performing the gyro followed by a simple move. On this puzzle, a gyro is usually about six physical twisting actions, but on other puzzles, they can be more complicated, so finding a puzzle that supports a short gyro is valuable.

Restricted 25¶

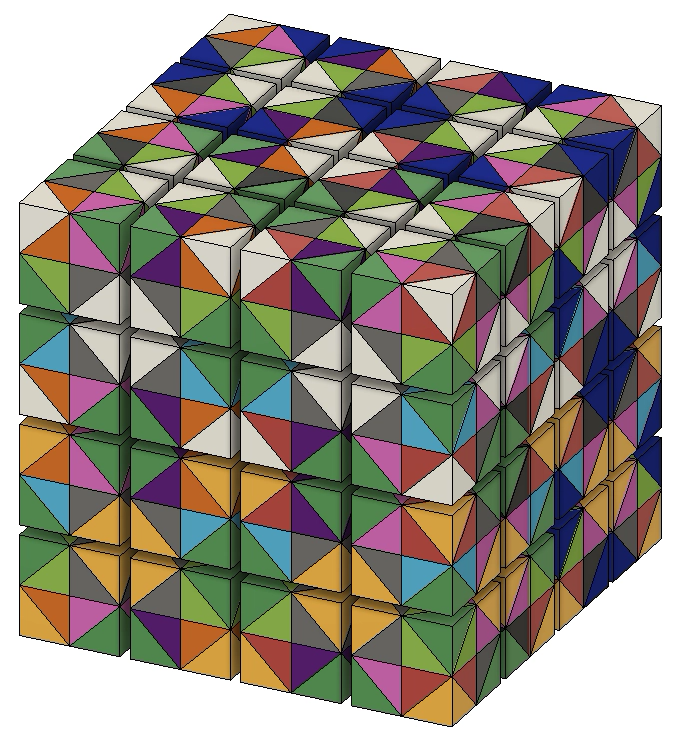

The pieces of a virtual 25 have 60 orientations, the even permutations of its 5 stickers. It is difficult to design a piece with this symmetry, so the restricted 25 sets one axis to be unswappable with the others, i.e. it is a 24x21 in the notation of the previous section. This means the pieces only need to be able to evenly permute 4 of their stickers, which is the same symmetry as the pieces of the physical 24. The pieces from that can thus be reused to build the restricted 25, with one sticker added to each piece. The extra sticker needs to be invariant under all rotations of the piece, so it needs to be applied to every face of the piece.

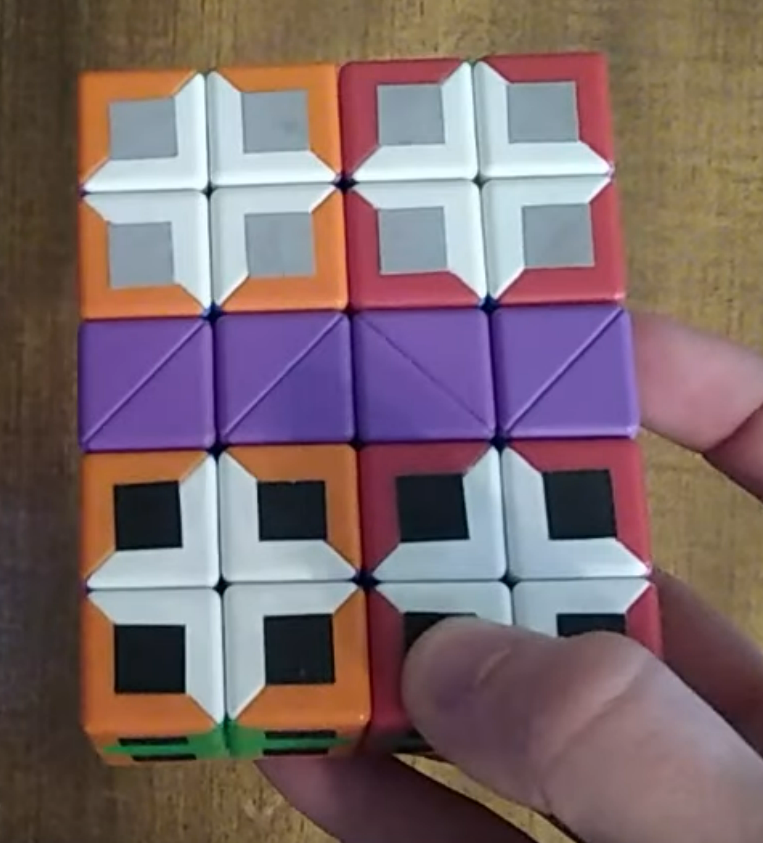

The design of the puzzle is simple: two copies of the physical 24, where the legal moves are doing a whole puzzle rotation on one, doing the same twist on both, or swapping 8 pieces from each half by twisting a side of the puzzle. The design requires a buffer layer (pictured above in purple), because if it were not present, doing a 90° rotation of the whole puzzle corresponds to three moves on the virtual restricted 25, which is considered illegal in solves.

Unrestricted 25¶

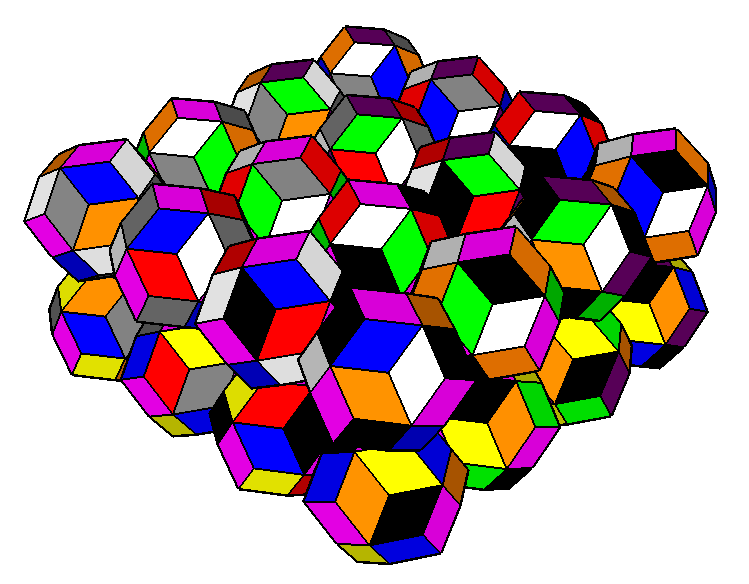

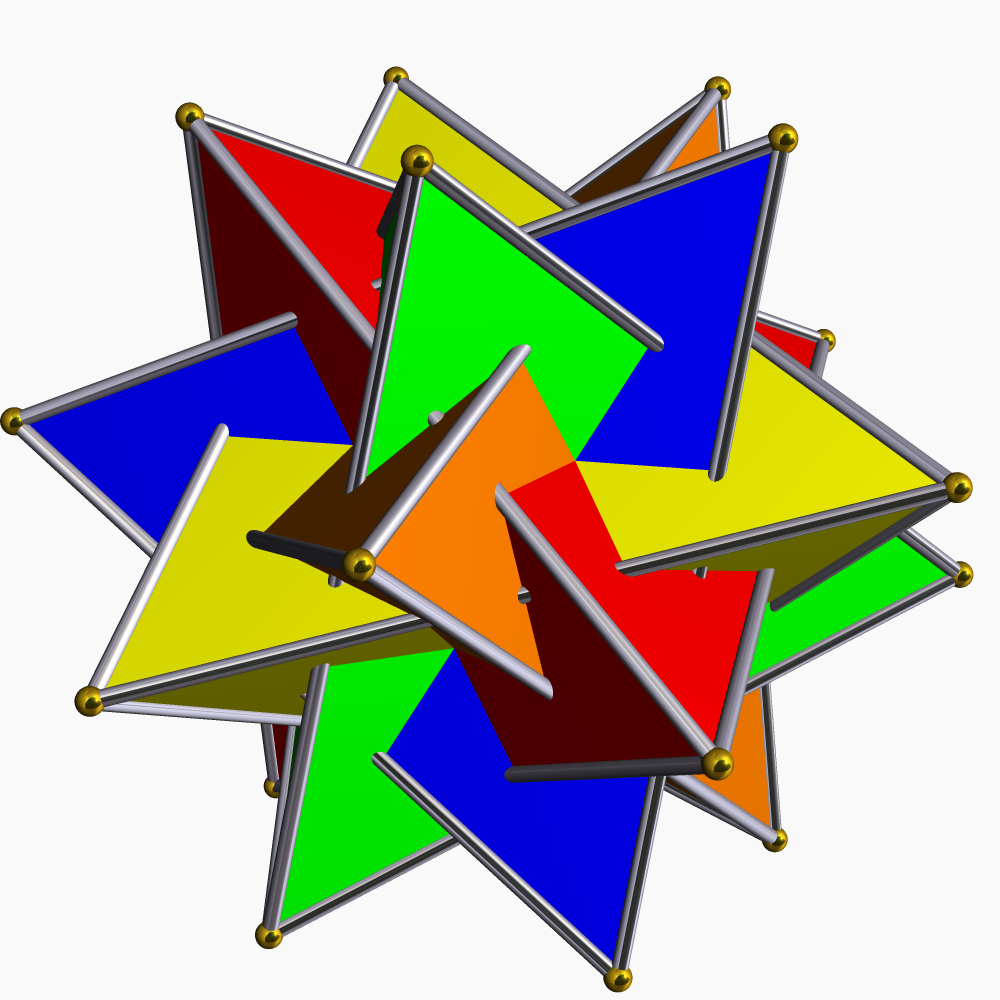

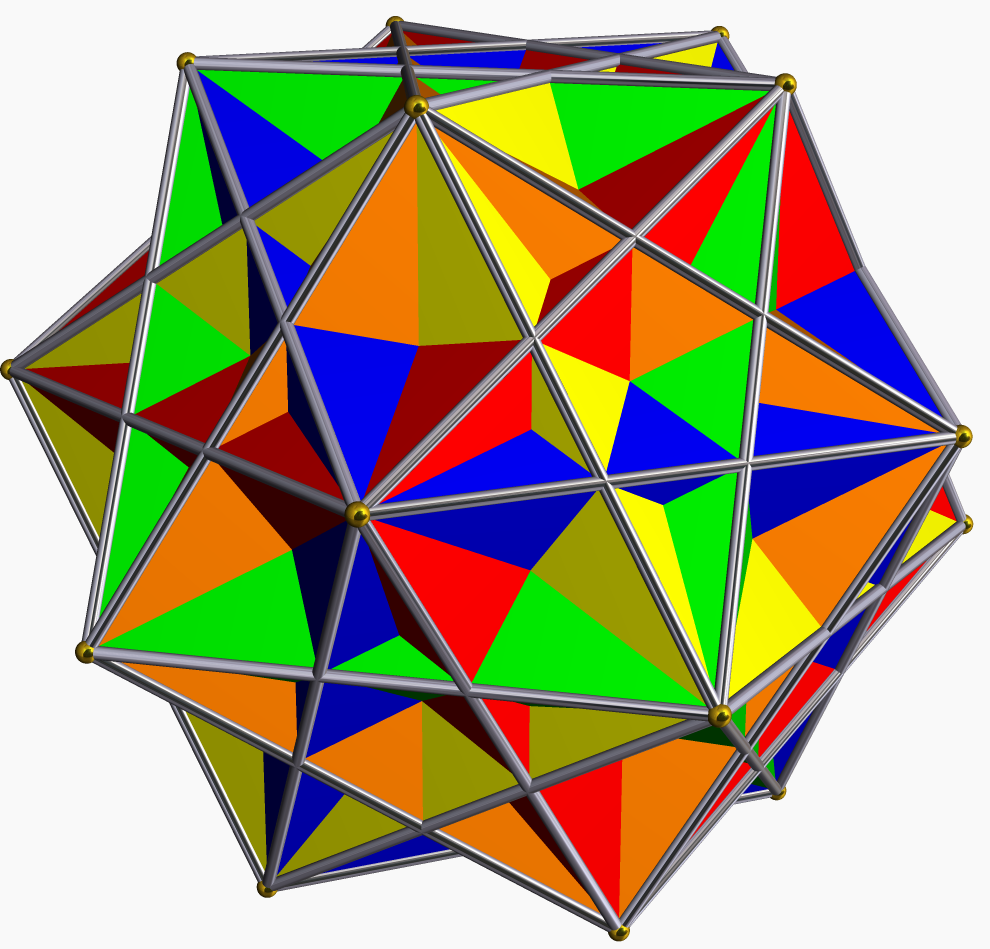

It is not impossible to design a piece with 5 stickers that supports all even permutations of its stickers. The symmetry group of this piece is called \(A_5\), the alternating group on 5 points, and it is isomorphic to the symmetry of the icosahedron. It is not obvious whether there are actually 5 objects permuted by this group, but there are: the 5 tetrahedra of the compound of 5 tetrahedra, or the 5 cubes of the compound of 5 cubes. Any even permutation of the 5 components of either shape can be realized as a rotation of the whole shape.

The compounds of 5 tetrahedra and 5 cubes1

Observe that in the compound of 5 cubes, if you take one cube as fixed, the other four cubes each share one pair of opposite vertices with it. In particular, the arrangement of these 4 other cubes has the same symmetry as the 4 stickers of the piece of the physical 24, or the 4 exchangeable stickers of the restricted 25. Thus, by designing a piece based on this object, the true physical 25 can be implemented that shares all the moves of the restricted 25, along with one new gyro move. Because of the complexity of the puzzle, the gyro is very difficult to execute.

26¶

The virtual 26 has pieces, which have 6 stickers each. Each piece must be able to perform all even permutations of all 6 stickers, which results in the group \(A_6\) of order 360. A rigid piece in 3 dimensions must have as its symmetry a chiral point group. However, the only discrete chiral point groups in 3 dimensions of order 360 all contain a rotation by \(\frac{\pi}{90}\), which has order 180. \(A_6\) has no elements of order 180, so none of these point groups are isomorphic to \(A_6\), and a physical 26 with rigid pieces is impossible. (The lowest dimension to have an object with the requisite symmetry is 5, with the 5-simplex.)

This does not preclude other designs for a physical 2^6 that have not been developed yet. For instance, a skewb has 6 center pieces, and all even permutations of them are accessible with skewb twists. This means that skewbs can be used as pieces for a physical 26. Whether there is a design for it that does not require manipulating the individual pieces every turn is unknown.

Restricted 26¶

There are several ways to restrict a 26 to make it able to be made physical. One way is to make it a 25x21, which can be made physical out of two copies of the 25 in the same way as the 24x21 was made out of the 24. Another way is the 24x22, pictured above. Each piece of the 24x22 has four 4-stickers and two 2-stickers. The four 4-stickers can have an even permutation applied to them, or the two 2-stickers can be swapped and an odd permutation can be applied to the four 4-stickers. This enlarges the symmetry group of the piece from \(A_4\) to \(S_4\), the symmetric group on 4 points. Fortunately, octahedral symmetry acts on the four space diagonals of a cube by \(S_4\), and one endpoint from each diagonal corresponds to the vertices of a tetrahedron, used for the stickers on the 24. Therefore, the 4-stickers can be placed on opposite corners of a cube. The stickers on the periphery of the pieces correspond to the 2-stickers, which swap whenever the piece is rotated in a way that does not preserve the original tetrahedron, i.e. one that does an odd permutation. It may require one or more buffer layers.

-

Images created with Stella software. ↩